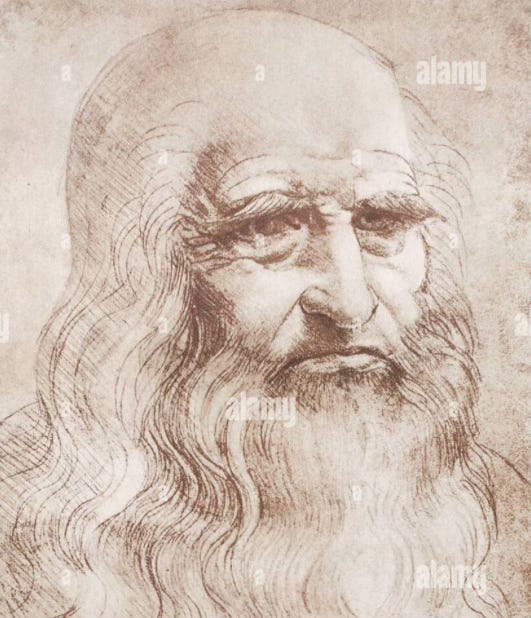

Leonardo Da Vinci’s Curious Voyage: How Aimless Wandering Leads to Somewhere Unique

Great art captures impermanence and makes it permeant

I am currently immersed in Walter Isaacson's biography of Leonardo da Vinci. The main reason I chose this biographer was my interest in discovering Da Vinci’s personality and character. I wanted to see if the great hero of Renaissance Italy was a disciplined overachiever. Instead, I discovered a distracted, wandering polymath more interested in pursuing his own curiosity than in accomplishing things. So much so that he wrote in his notebook near the end of his life: “Tell me if anything was ever done. Tell me if anything was ever made. Tell me if I ever did a thing.” The great Renaissance hero was full of self-doubt, afraid of the triviality of his own life, afraid no trace would remain.

You probably know that he was an incredible polymath, but you might still underestimate this. Here are a few examples:

Study of Optics: This helped him tremendously in painting. He mastered the sfumato style through his analysis of optics, realizing that light hits the retina at multiple points. He wrote that humans perceive reality without sharp edges and lines. In contrast to Michelangelo, who delineated objects by first painting a line, Da Vinci used subtle shades of light. Nowhere is this better seen than in The Last Supper. The contrast with other works in the same building is striking. There you will see the meaning of the word talent. You will see what cannot be taught. Other paintings may be technically perfect, but compared to Da Vinci's, they look rigid and unnatural.

Study of Water: He designed a water pump to drain marshes.

Study of Anatomy: This also helped him tremendously in his painting. He realized that the heart was a muscle and a pump, though he didn’t fully understand blood circulation. He noticed differences in arteries between younger and older people, comparing them to fresh and dried oranges. He injected wax into arteries to prevent decay, a practice not seen for another 200 years. His experience as a sculptor likely inspired this idea.

Study of Nerves: He investigated which nerves originated in the brain and which in the spinal cord.

Study of the Flight of Birds

Study of Astronomy

Study of Fossils: He found fossils in the Apennine mountains and surmised that the sea must have once been present there. He also deduced that the number of lines on a fossil reflected the animal's age, similar to tree rings.

He wrote pages of treatises on flying machines, tanks, and diverting rivers. The list is even longer, but this suffices to show the breadth of his curiosity.

He didn’t often publish his findings. As Isaacson says, “he was more interested in pursuing knowledge than publishing it.” Maybe this is why many of his ideas had to be rediscovered hundreds of years later, or perhaps the technology and materials of his time didn’t permit concrete applications from his findings.

Reading this biography, one gets the impression that he went off in different directions almost daily. This is evident from his ‘to-do’ lists:

"Draw Milan."

"Get the master of arithmetic to show you how to square a triangle."

"Ask Giannino the Bombardier about how the tower of Ferrara is walled."

"Get a skull."

"Describe the jaw of a crocodile and the tongue of a woodpecker."

He filled pages of his notebook with 169 attempts to square a circle.

When he returned to Florence after many years in Milan, he apparently never wanted to pick up a paintbrush. He presented himself to rich patrons as an engineer, but they wanted to hire him as a painter. When he lived in Rome, Pope Julius II reportedly said that Da Vinci was very talented, but wondered if he ever got anything done.

History remembers him primarily for his art. Would he have been known otherwise? People are often remembered for vanity, not curiosity. Art was, after all, a form of vanity in Renaissance Italy. It immortalized the subject of a portrait before the invention of the camera and embellished palaces to show off wealth.

His curiosity, his desire to understand many things in one field, helped him excel in another. This is evident in the idea that what is not visible influences what is visible.

To quote Isaacson: “In the Mona Lisa, he painted the embroidered pattern of the lattice of her dress, even in places where he would cover it with a layer of garment so we can faintly sense its presence even where we cannot see it.”

Real curiosity and a love of doing are what bring the greatest results, even without financial reward. They are the invisible ingredients that lead to lasting accomplishments, like the secret ingredient in a sauce that makes all the difference. He never delivered the Mona Lisa, never collected any money for it. He had it in his possession when he died and probably painted it for himself over many years. The Mona Lisa captures the essence of its subject, making the impermanent permanent.

In contrast, Isabella d'Este, a wealthy and influential noblewoman, was eager to have her portrait done by Da Vinci. Despite her many requests and significant influence, he never completed a formal portrait of her.

Great things are done only when one follows one’s curiosity.

The butterfly effect is the idea that small changes in a system can have large and unpredictable consequences. The term was coined by Edward Lorenz, a mathematician and meteorologist, in the 1960s.

The butterfly effect is a reminder that we are all interconnected and that our actions can have far-reaching consequences. It is also a reminder that we should be careful about making assumptions about the future, as even small changes can have big impacts.